Appendices

Appendices

1. Glossary

For a glossary describing relevant concepts and key words used in the global research and action agenda, please download from here.

2. Background Context

Connecting Climate Minds

Connecting Climate Minds (CCM) is a Wellcome-funded initiative to cultivate a collaborative, transdisciplinary climate and mental health field with a clear and aligned vision.14

CCM aims to:

- Develop an aligned and inclusive agenda for research and action that is grounded in the needs of those with lived experience of mental health challenges in the context of climate change, to guide the field over the coming years.

- Kickstart the development of connected communities of practice for climate and mental health in seven global regions (designated by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)) that are equipped to enact this agenda.

We convened over 950 diverse experts in 2023 across research, policy, practice and lived experience in over 90 countries to develop Regional and Lived Experience Research and Action Agendas. These Agendas were launched in March 2024 and set out 1) research priorities to understand and address the needs of people experiencing the mental health burden of the climate crisis, and 2) priorities to enable this research and translate evidence into action in policy and practice. The seven Regional and three Lived Experience agendas have been synthesised as the basis for the global agenda.

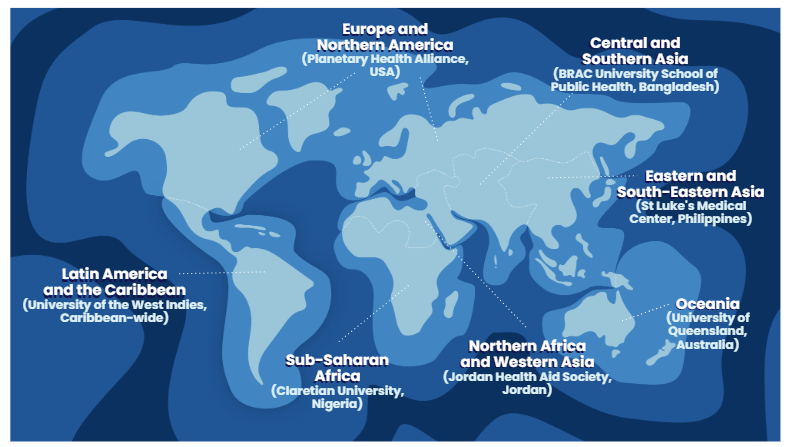

Supported at a global level by the Climate Cares Centre at Imperial College London and the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre, Regional Communities of Practice (Figure 7) were developed in seven regions (Sub-Saharan Africa, Northern Africa and Western Asia, Central and Southern Asia, Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Oceania, and Europe and Northern America). Each Regional community consisted of a Regional Community Convenor, Co-Convenors, Lived Experience Advisory Group and Youth Ambassador(s), supporting a regional network of dialogue participants. A Lived Experience Working Group worked with partner organisations and advisors to lead the creation of three lived experience Research and Action Agendas by and for youth, Indigenous Communities and small farmers and fisher peoples. A Global Advisory Board oversaw the initiative. Development of the Global Agenda was also guided by a global Expert Working Group.

Figure 7: Regional communities of practice were formed in the seven Sustainable Development Goal regions, led by Regional Convenors.

Conceptualising Mental Health

Understandings of mental health span disciplines and cultures in complex and wide-ranging ways. For the purpose of this Agenda, we define the scope of relevant terms as follows.

By mental health challenges, we mean thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that affect a person’s ability to function in one or more areas of life and involve significant levels of psychological distress. This includes, but is not limited to, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, psychosis, suicidal thoughts, and substance misuse.

Climate change may…

- Lead to worsening pre-existing mental health challenges.

- Contribute to an increased prevalence of mental health challenges.

- Impact treatment access or effectiveness for those with mental health challenges.

- Lead to novel mental health challenges.

Whether and when a response to a climate change-related experience is healthy, rational and adaptive, and/or exacerbates or causes mental health challenges that may require support is a key question within this Agenda. While it is imperative to not pathologise distress that is proportional to the severity of the threat faced, it is vital that people experiencing on-going climate change-related challenges to their mental health receive appropriate support, and that people living with severe mental health challenges receive appropriate attention in research and action as a particularly at risk group that has received insufficient amounts of attention to date.

This agenda also recognises that the understanding and expression of mental health in different cultures and contexts will vary, and must be centred when applying this Agenda. For instance, Indigenous Peoples and Nations often include emotional, spiritual, social and cultural health as indivisible from and core tenets of the concept of mental health33,34. The convening work of CCM presents a key opportunity to build our understanding of diverse perspectives, framings and terminologies, which we have sought to reflect within the global agenda (Box 2).

| Box 2: Examples of definitions of mental health provided by CCM participants at the Global Event: Mental health is… “Ability to function behaviorally and socially and maintain a general feeling of wellbeing and positive emotions” “A mind that is able to function optimally for self and society.” “Good cognitive processing and emotional regulation that fosters connectedness” “The unseen space of our humanity that involves emotions, spirituality, and relationships” |

|---|

Conceptualising Climate Change

By experiences of the effects of climate change, we mean: 1) directly experiencing the impact of climate hazards, such as more frequent and intense heat waves, wildfires/bushfires, drought, floods, or storms (e.g., typhoons, hurricanes, cyclones), and 2) experiencing climate change-related disruption to the social and environmental determinants of good mental health, such as being forced to move home, not being able to access food or water, losing livelihood or homelands, or disruption to cultural practices.

Global-scale current and emerging environmental risks associated with climate change

A global-scale synthesis of environmental risks associated with climate change was conducted by the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre and is summarised below:

- Extreme heat: defined here as days with daily maximum temperature (Tmax) above 35°C, extreme heat is emerging as a rapidly growing risk across most regions globally.49 Historically, extreme heat has affected a large proportion of the global population especially in the lower latitudes, such as the low-income regions of South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.50 In addition, recent decades (for instance in the 2010s and more recent years such as 2022 and 2023) have seen unprecedented heatwaves in higher latitude regions such as in Europe, North America and Australia. In general, climate models show a strong agreement (i.e., high confidence) with most regions projected to see an increase in extreme heat in the near future.51 Combined with the rise in population especially in major urban areas globally, we are also likely to see more vulnerable people (e.g., the infants and the elderly) at risk from this meteorological hazard in the coming decade.

- Flood and landslide: Another prominent risk that stands out in terms of the number of people affected at a global scale is from surface water and river flooding. Among the regions that stand out in terms of occurrence of flooding in recent years are Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe and North America, and Central and South Asia.52 However, unlike for temperature, climate models generally demonstrate only moderate agreement (implying medium confidence) when projecting changes in the number of days with heavy rainfall across most regions.54 Nevertheless, flooding can cause widespread damage both to life and property. Landslides, often associated with extreme rainfall events, have also seen a global scale increase in recent years. Unlike temperature and rainfall, both flooding and landslide are not direct outputs of climate models and instead need to be combined with additional terrain information among others to estimate the likelihood of changes in the future. Thus, the projected changes in both flood and landslide remain difficult to model directly and tend to exhibit less certainty unlike the projected changes in extreme heat.

- Storm: With a rise in the global mean sea-surface temperatures especially in the tropics, recent decades have seen a subsequent increase in the number of storms. More importantly, storms have also increased in strength due to the additional energy provided by the warming sea surface, with an increasing number of storms especially in South-East Asia and Latin America also making landfalls resulting in loss of life and property in recent years. Most storms form in a narrow belt of latitudes around the equator and then chalk a clockwise and anti-clockwise path in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres respectively. While such paths or storm tracks are difficult to predict beyond a few days ahead, conditions favourable for development of intense storms (such as wind shear and thermal energy associated with warming on sea surface) are better captured by models. In general, coastal regions in the tropics are projected to see an increase in more severe storms, with the small-island nations also at risk from associate storm surge. It must be emphasised though that the agreement across models remains low, implying a general low confidence in projected changes in the frequency and magnitude of the storms in the future at a global scale.

- Drought and wildfire: Closely associated with extreme heat, drought and wildfires have seen spatially varying changes in recent years. In Europe and North America in particular, recent extreme heat associated with arid conditions have resulted not only in prolonged droughts (e.g., Spain), but also increasingly favourable conditions for wildfires to spread once caused either due natural causes (lightning) or by humans. Recent years have seen unprecedented swaths of forests affected by wildfires in North Africa, Europe, the Amazons, Equatorial Africa and South-East Asia. While modelling the ignition risk of wildfire remains challenging as most wildfires are started by humans, the underlying fire weather, which is a mixture of arid and hot conditions, is projected to become more favourable, though with regional disparities. Climate models generally show a moderate level of agreement (medium confidence) in projecting droughts in a number of regions across the globe, in particular for the Mediterranean and Central Europe.

- Sea level: Finally, a number of small island nations, especially in the Pacific, remain at risk from rising sea levels in a warming climate (medium confidence).53 Though the population exposed in such small nations may not be comparable to the population at risk from other categories of hazards, their communities nevertheless remain highly vulnerable from sea level rise that are often most difficult to adapt to in a warming climate.

3. Detailed Methods

Key stages of developing the CCM regional and global research and action agendas are outlined below.

- Pre-dialogue scoping, development of a global framework of research categories and formation of networks: A global mapping exercise of relevant actors, disciplines and sectors informed the formation of regional and global project teams and networks. A review of the current climate and mental health academic evidence base2,26,44,55–61 and policy landscape1,3,21,44,56,59,62–66 by the Climate Cares Centre, Imperial College London informed the development of a global framework of research categories. This framework contained four broad high-level research categories that were identified as areas of critical need for further work globally. This was used as the basis for structuring discussions within dialogues to generate research and action priorities and informed the global coding framework for analysis. Regional and thematic teams conducted lived experience perspective gathering, scoping reviews of relevant literature, key informant interviews and surveys to inform dialogue design and relevant adaptation of the analysis framework.

- Regional and lived experience dialogues: diverse experts were convened across disciplines, sectors, lived experiences and geographies to surface relevant needs, priorities for research, and pathways to implementing and translating research. Each region conducted two, three hour dialogues using Zoom, between August and November 2023. The Lived Experience dialogues included 3 in person (Peru, India and Nigeria) and 4 online dialogues between September and November, 2023.

- Dialogue content analysis: Dialogue data was qualitatively analysed to identify priority research topics (research agenda) and challenges, opportunities, key partners and priority actions to implement and translate research (action agenda). The analysis was conducted by representatives from each of the regional and lived experience groups, with support from the global team.

- Development of the regional and lived experience research and action agendas: Results from the dialogue content analysis were written up into summary and long version agendas, in consultation with relevant experts across regions and global communities.

- Synthesis of the ten regional and lived experience agendas: the draft global research agenda was developed by Climate Cares based on a qualitative synthesis of all research priorities from the ten regional and lived experience research and action agendas. The same global framework of high-level research categories was used for an analysis that combined inductive and deductive approaches to identify priority research topics and questions within each category for the global research agenda. The draft global action agenda was developed based on a qualitative synthesis of the challenges, opportunities and vision statements outlined in the ten regional and lived experience research and action agendas.

- Iteration of the draft global research and action agenda: the draft global research and action agenda was iterated based on multiple feedback rounds with an expert working group, with authors of the ten regional and lived experience research and action agendas, and at the CCM Global Event in March 2024.

- Prioritisation survey: an online survey was distributed across the CCM regional and global community teams, advisors and other relevant global experts, and was used to identify the top two priority research questions within each high-level category, and as a final round of qualitative feedback.

- Finalisation of the global research and action agenda: the global research and action agenda was finalised based on review from contributors across sectors and disciplines, as well as inputs by Wellcome.

Ethics, Data Collection and Storage

Ethics

This study has been reviewed and given an ethical favourable opinion by the Imperial College Research Ethics Committee (Study title: ‘Global Dialogues to set an actionable research agenda and build a community of practice in climate change and mental health’, study ID number: 6522690).

Data collection, storage and sharing

Dialogues were conducted virtually on Zoom following informed consent from all participants. Survey distribution and data collection was carried out using the online platform Qualtrics. Data was stored and managed by Imperial College London using a secure server.

Regional Community Convenors are Joint Data Controllers for the data provided to this project for each region, and responsible for securely storing and sharing data with Imperial College London and with regional analyst teams. Research data for the youth research and action agenda was collected by SustyVibes and Force of Nature and then transferred to Imperial College London. Research data for the Indigenous community and small farmers and fisher peoples agendas was collected by the Climate Mental Health Network and then transferred to Imperial College London. Kichwa communities in San Martin, Peru and Kom village in Cameroon are Joint Data Controllers for the data their community members provided to this study, and were responsible for gathering, storing and sharing this data with the Climate Mental Health Network and Imperial College London.

Data will be stored by Imperial College London for 10 years after study completion.

Strengths and Limitations

This project's strength lay in the breadth and diversity of the networks it brought together; most regional dialogues had equal contributions from the climate and the mental health spaces, which has been an imbalance in the field. The focus on regional leadership and community building helped progress in addressing the uneven nature of the Global North-heavy literature, and lived experience was centred throughout, led by a dedicated Lived Experience Working Group. Doing so in appropriate ways required embedding processes that were new to Global North institutional norms, such as collective consent and data sharing that accounted for and globally applied Indigenous data sovereignty standards. The awareness raising, capacity building and strong connections forged through CCM has created an enthusiastic global community better equipped and poised to enact this agenda.

While the project attempted to address unevenness and biases which hold back the climate and mental health field in its design, some biases - perhaps inevitably given the scale and entrenchment of these challenges - arose in who contributed to the global agenda. Expert working group and survey contributions, for example, predominantly came from Europe and Northern America. Dialogues held mostly virtually may also have been a barrier to participation. A further challenge, imperfectly met, was balancing the urgency to develop a research and action agenda for this growing field with moving at the pace of trust and prioritising relationship building and meaningful convening. This is particularly important for groups frequently subjected to extractive research processes (i.e. Indigenous communities), and was supported by the Lived Experience Working Group. Finally, in synthesising diverse perspectives, this agenda acknowledges that it cannot perfectly capture the richness of different definitions and expressions of mental health highlighted in CCM.

4. Prioritisation Survey Results (Priority Research Questions)

Using an online survey, global experts were asked to select their top three priority research questions within each of the four high-level research categories. The survey was shared with the CCM community of Regional Community Convenors and advisors, the global agenda expert working group, Global Advisory Board, and those who held expertise in disciplines that had been less well represented at that point in the global agenda development (e.g. neuroscience). This data was analysed to identify the three priority research topics in each category which were selected the most, of which the top two are reported in the main body of this agenda.

Details of survey participants are shown in Table A1.1-A1.5.

| Table A1.1: Region | Number of survey respondents | Proportion of survey respondents (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 10 | 14 |

| Northern Africa and Western Asia | 3 | 4 |

| Central and Southern Asia | 3 | 4 |

| Eastern and South-Eastern Asia | 9 | 12 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 5 | 7 |

| Oceania | 8 | 11 |

| Europe and Northern America | 36 | 49 |

| Table A1.2: Area of Expertise | Number of survey respondents* | Proportion of survey respondents (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Climate change | 48 | 65 |

| Health | 44 | 59 |

| Mental health | 44 | 59 |

| Other | 19 | 26 |

| *Survey respondents were able to select more than one option |

| Table A1.3: Type of work | Number of survey respondents* | Proportion of survey respondents (%)* |

|---|---|---|

| Research | 61 | 82 |

| Policy | 37 | 50 |

| Advocacy / Activism | 31 | 42 |

| Education / Teaching | 30 | 41 |

| Non-governmental organisation / Community organisation | 29 | 39 |

| Expert through own lived experience | 16 | 22 |

| Healthcare | 14 | 19 |

| Funding | 12 | 16 |

| Other | 3 | 4 |

| *Survey respondents were able to select more than one option |

| Table A1.4: Gender | Number of survey respondents | Proportion of survey respondents (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Woman (including transgender woman) | 52 | 70 |

| Man (including transgender man) | 18 | 24 |

| Non-Binary | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 2 | 4 |

| Table A1.5: Personal experience of mental health challenges in the context of climate change | Number of survey respondents | Proportion of survey respondents (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No personal experience | 16 | 22 |

| Some personal experience | 40 | 55 |

| A lot of personal experience | 16 | 22 |

A regional weighting was applied to account for regional bias in survey responses, which were particularly skewed towards responses from Europe and Northern America (where there are the most existing researchers focussed specifically on climate and mental health). However, the small number of survey respondents and large skew in regional responses resulted in both very large and very small weights, posing an issue for interpretation of this weighted analysis. Top priorities reported in the main body of the global research and action agenda therefore represent either 1) the two research questions where there was alignment between unweighted and weighted data within the overall top three research questions (this is true for 3 high-level categories), or 2) when there was not alignment between unweighted and weighted data for the top two research questions, the unweighted research question is reported (this is true for category 2) (Table A2). Readers should be mindful, therefore, that featured priority research questions in Figure 4 represent mostly the views of experts based in Europe and Northern America.

| Table A2: Results of a survey used to identify global experts’ top three priority research questions in climate and mental health, within four high-level categories Colour code: Yellow = top three priority when regional weighting applied and when regional weighting not applied; Light blue = top three priority only when regional weighting is not applied; Dark blue = top three priority only when regional weighting is applied. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted | Regionally Weighted | |||

| High level category one: Impacts, risks and protective factors | Number of survey respondents who selected this research question as one of their top 3 | Percentage (%) | Number of survey respondents who selected this research question as one of their top 3 | Percentage (%) |

| 1.1.1 Risk and protective factors | 40 | 56 | 34 | 48 |

| 1.3.1 Attributing costs | 34 | 47 | 31 | 43 |

| 1.2.2 Disruptions to determinants | 31 | 43 | 27 | 38 |

| 1.2.5 Long-term impacts | 23 | 32 | 28 | 39 |

| Unweighted | Weighted | |||

| High level category two: Pathways and mechanisms | Number of survey respondents who selected this research question as one of their top 3 | Percentage (%) | Number of survey respondents who selected this research question as one of their top 3 | Percentage (%) |

| 2.7.1 Interactions between different pathways and mechanisms | 16 | 22 | 19 | 25 |

| 2.2.7 Influence of structural inequalities | 20 | 27 | 13 | 17 |

| 2.7.2 Risk, protective, mediating and moderating factors | 12 | 16 | 10 | 14 |

| 2.5.4 Genetic and epigenetic changes | 9 | 12 | 14 | 19 |

| 2.2.3 Disruptions to culture and identity | 9 | 12 | 14 | 18 |

| Unweighted | Weighted | |||

| High level category three: Mental health risks and benefits of climate action | Number of survey respondents who selected this research question as one of their top 3 | Percentage (%) | Number of survey respondents who selected this research question as one of their top 3 | Percentage (%) |

| 3.3.1 Best-buy interventions for enabling co-beneficial climate action | 37 | 51 | 38 | 53 |

| 3.2.1 Community involvement and leadership in climate action | 23 | 32 | 26 | 37 |

| 3.1.2 Climate adaptation | 28 | 39 | 21 | 29 |

| 3.2.2 Transdisciplinary collaboration and knowledge sharing | 23 | 32 | 32 | 44 |

| Unweighted | Weighted | |||

| High level category four: Mental health interventions in the context of climate change | Number of survey respondents who selected this research question as one of their top 3 | Percentage (%) | Number of survey respondents who selected this research question as one of their top 3 | Percentage (%) |

| 4.5.1 Best-buy interventions for extreme weather and climate events | 25 | 34 | 27 | 37 |

| 4.4.1 Effective approaches for risk reduction and response across sectors | 29 | 40 | 26 | 36 |

| 4.1.1 Existing interventions | 23 | 32 | 19 | 26 |

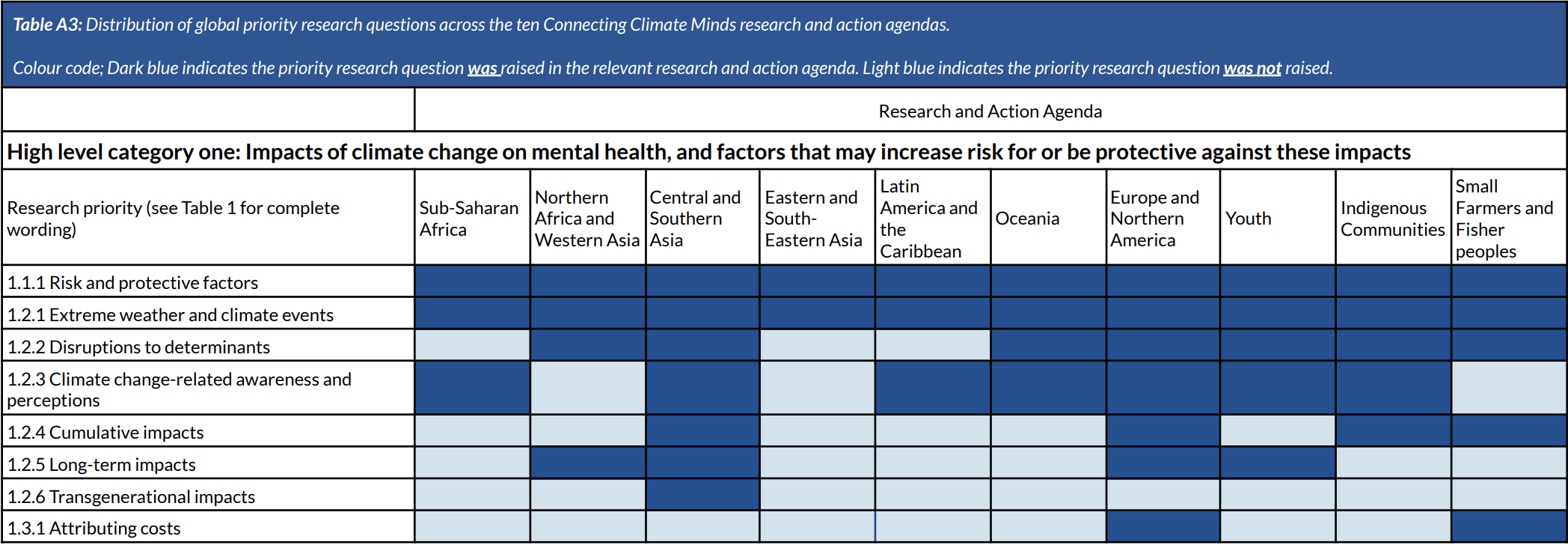

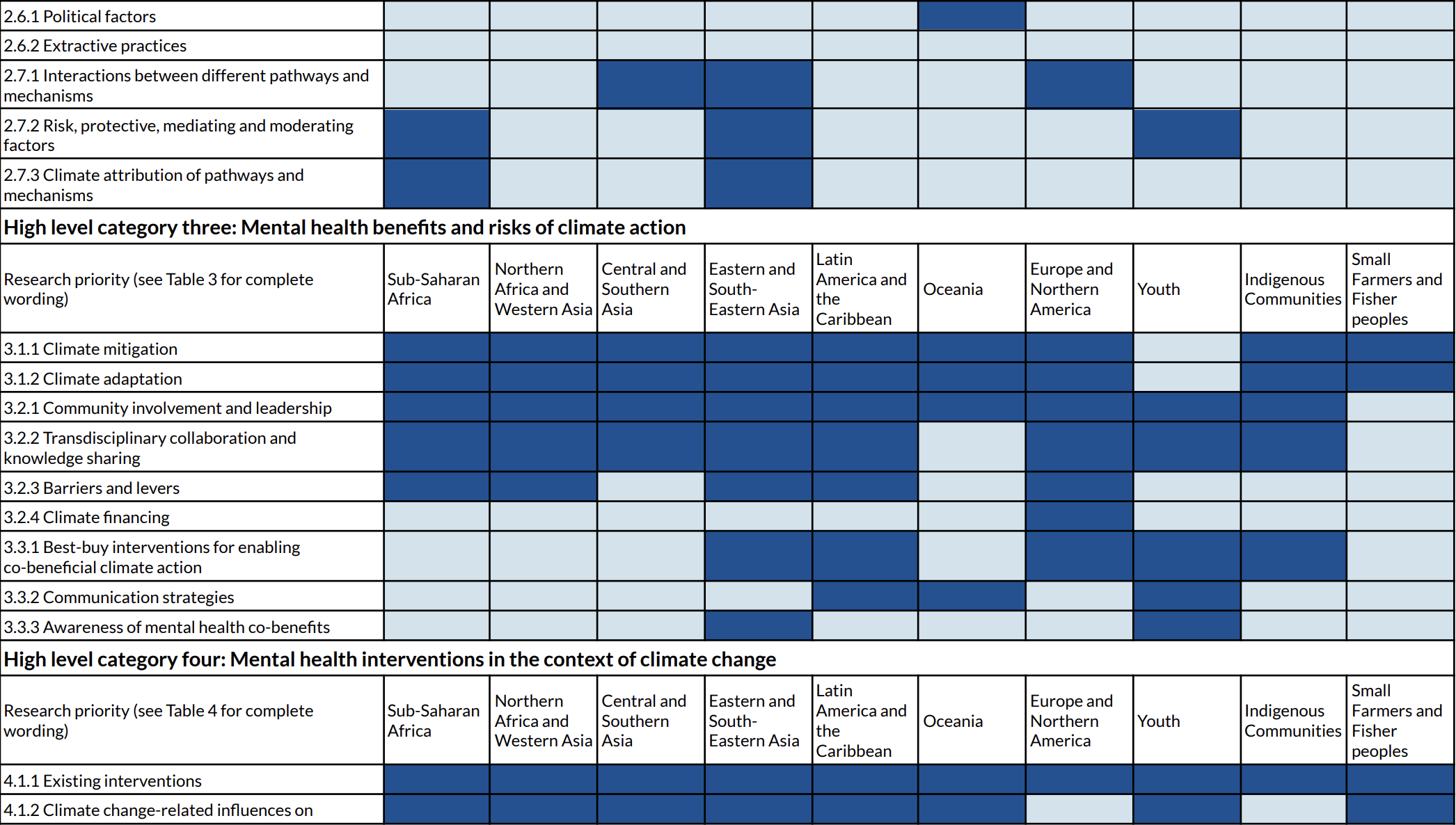

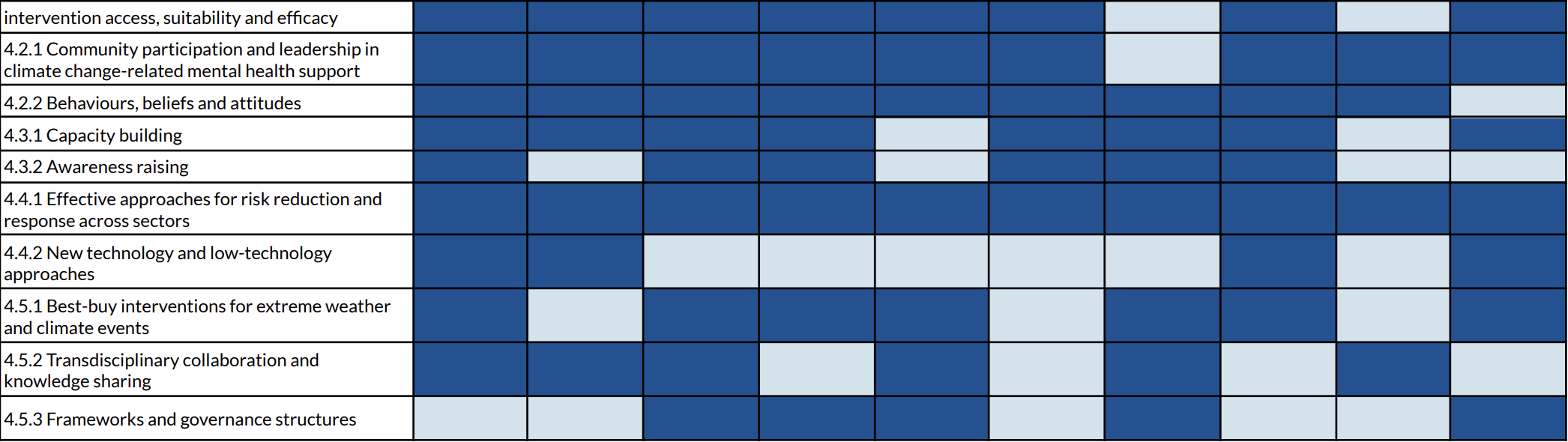

5. Global Research Agenda: Regional Analysis

In Table A3, each priority research question is shown alongside a breakdown of which of the ten CCM research and action agendas - in seven SDG regions and with youth, Indigenous communities and small farmers and fisher peoples - that research priority was raised in. An average for the research questions within each research topic was generated to indicate level of inclusion across the ten agendas per topic. This has determined the order in which research topics are presented in the global agenda.

6. Applying the global research agenda: Population groups, mental health challenges and extreme weather and climate events

The global research agenda must be applied with consideration of different climate exposures across different contexts, the full spectrum of mental health challenges that may be caused or worsened by climate change, as well as of the different population groups that may be most affected.

Table A4 presents a synthesis of population groups, mental health challenges and extreme weather and climate events which emerged throughout the CCM process, as identified in previous literature, dialogues or from the expert working group. Other particular population groups or mental health challenges to those listed may need to be considered or may become more significant over time so researchers should always seek to understand the current context (including relevant sub-groups), as it exists locally, and centre the experiences of the population groups the research aims to benefit.

| Table A4: Population groups, mental health challenges and extreme weather and climate events which emerged throughout the Connecting Climate Minds process as particularly relevant for when considering how to adapt global research questions across contexts | |

|---|---|

| Population groups and characteristics mentioned with potential for unique vulnerabilities to the mental health impacts of climate change as well as unique sources of resilience These attributes also intersect and many people will be living with multiple vulnerabilities and resiliencies. | Health-related vulnerabilities: People with pre-existing mental health challenges, people with pre-existing physical health conditions Disability-related vulnerabilities: People living with long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments Occupations with high vulnerabilities (including informal and unpaid occupations): Small farmers, fisher peoples, people working in informal sectors, people working outdoors, health workers, first responders and emergency service providers, people working in climate change-related professions or studying related subjects, climate activists, people in caring roles Gender/sexuality-related vulnerabilities: Women, including in particular pregnant and breastfeeding women, single female household heads, LGBTQI+ communities, non-binary people Race/ethnicity related vulnerabilities: People from minority ethnic, racial or religious groups in the area that they live, Indigenous communities Socioeconomic vulnerabilities: People living in informal or temporary settlements, people experiencing homelessness, people living in conflict zones, people living in areas with insufficient health services or difficulties to access health services, refugees and migrants, people from less privileged socioeconomic groups, people with low levels of education Geographic vulnerabilities: People living in areas at high risk of extreme weather and climate events (e.g. coastal areas prone to flooding and rising sea levels, drought and fire-prone regions). People living in remote and/or rural areas (including areas with limited internet/telecommunication receptions) Age and life stage related vulnerabilities: Prenatal development, infanthood, childhood, adolescence and emerging adulthood, older adulthood, perinatal and new parenthood Institutional setting vulnerabilities - People residing in prisons, long-stay mental health care institutions, immigration detention facilities, care homes |

| Mental health challenges Mental health challenges are defined in Connecting Climate Minds as thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that affect a person’s ability to function in one or more areas of life and involve significant levels of psychological distress. | Mental health disorders, including: (ICD-11)67 Mood disorders including Major Depressive Disorder Anxiety or fear-related disorders including Generalised Anxiety Disorder Disorders specifically associated with stress including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Disorders due to substance use or addictive behaviours Schizophrenia or other primary psychotic disorders Transdiagnostic presentations, including: Suicide Self harm Sleep disruptions **Mental wellbeing impacts *(*while not mental health challenges themselves, these psychological and emotional responses may lead to impacts on daily functioning, reduce quality of life and the ability to thrive, interact with mental health challenges, and/or lead a person to seek care), including: Stress Grief Mental wellbeing impacts specifically related to climate change, such as ecological grief, eco-anxiety, climate distress, climate anxiety, solastalgia etc. |

| Extreme weather and climate events Extreme weather event:”The occurrence of a value of a weather variable above (or below) a threshold value near the upper (or lower) ends of the range of observed values of the variable. The characteristics of what is called extreme weather vary from place to place in an absolute sense.” (IPCC, 2023)68 Extreme climate event: “The persistence of extreme weather for some time, such as a season.” (IPCC, 2023)68 This list includes extreme weather and climate events and also some impacts that result from these events. | Extreme heat (e.g. heatwaves, humid heat events (combination of high heat and humidity), night-time warming (high minimum temperatures)) Extreme rainfall and flooding Drought Wildfires / bushfires Tropical storms and hurricanes Sea level rise Salinization Glacial melt |

- Lawrance EL, Thompson R, Newberry Le Vay J, Page L, Jennings N. The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health and Emotional Wellbeing: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence and its Implications. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2022;34(5):443–98. doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2022.2128725

- IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056 pp., doi:10.1017/9781009325844.

- Lawrance EL, Massazza A, Pantelidou I, Newberry Le Vay J, El Omrani O. Connecting Climate Minds: a shared vision for the climate change and mental health field. Nat Ment Health. 2024;2:121–5.

- Kumar P, Brander L, Kumar M, Cuijpers P. Planetary Health and Mental Health Nexus: Benefit of Environmental Management. Ann Glob Health. 2023;89:49.

- IPCC 2023, Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 35-115, doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.

- Charlson F, Ali S, Benmarhnia T, Pearl M, Massazza A, Augustinavicius J, Scott JG. Climate Change and Mental Health: A Scoping Review. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2021;18(9), 4486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094486

- Gee G, Dudgeon P, Schultz C, Hart A, Kelly K. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Wellbeing. In: Dudgeon P, Milroy H, Walker R, editors. Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Wellbeing Principles and Practice. Commonwealth Government of Australia, Canberra; 2014. p. 55–8.

- World Health Organization. Frequently asked questions on the health and rights of Indigenous Peoples. World Health Organization. Available from: https://www.who.int/initiatives/global-plan-of-action-for-health-of-indigenous-peoples/frequently-asked-questions-on-the-health-and-rights-of-indigenous-peoples [Accessed 19.07.2024]

- Charlson F, Ali S, Augustinavicius J, Benmarhnia T, Birch S, Clayton S et al. Global priorities for climate change and mental health research. Environ Int. 2022;158:106984.

- Zhai P, Pirani A, Connors SL, Péan C, Berger S, Caud N, et al. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

- Davenport F, Burke M, Diffenbaugh NS. Contribution of historical precipitation change to US flood damages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021;118(4):e2017524118.

- Seneviratne SI, Zhang X, Adnan M, Badi W, Dereczynski C, Di Luca A, et al. Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

- IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056 pp., doi:10.1017/9781009325844.

- Fox-Kemper B, Hewitt HT, Xiao C, Aðalgeirsdóttir G, Drijfhout SS, Edwards TL, et al. Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

- Ranasinghe R, Ruane AC, Vautard R, Arnell N, Coppola E, Cruz FA, et al. Climate Change Information for Regional Impact and for Risk Assessment. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

- Ogunbode CA, Pallesen S, Böhm G, Doran R, Bhullar N, Aguino S et al. Negative emotions about climate change are related to insomnia symptoms and mental health: Cross-sectional evidence from 25 countries. Curr Psychol. 2023;42:845–54.

- COP28 UAE. COP28 UAE Declaration on climate and health. 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/cop28-uae-declaration-on-climate-and-health

- Alford J, Massazza A, Jennings NR, Lawrance E. Developing global recommendations for action on climate change and mental health across sectors: A Delphi-style study. J Clim Change Health. 2023;12:100252.

- Xue S, Massazza A, Akhter-Khan SC, Wray B, Husain MI, Lawrance EL. Mental health and psychosocial interventions in the context of climate change: a scoping review. npj Mental Health Res. 2024;3:10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44184-024-00054-1

- Massazza A, Teyton A, Charlson F, Benmarhnia T, Augustinavicius JL. Quantitative methods for climate change and mental health research: current trends and future directions. Lancet Planetary Health. 2022;6:7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00120-6

- UK Health Alliance on Climate Change. WHO adopts resolution stating climate change is a major threat to global health. UK Health Alliance on Climate Change. 2024. Available from: https://ukhealthalliance.org/news-item/who-adopts-resolution-stating-climate-change-is-a-major-threat-to-global-health/ [Accessed 19.07.2024]

- World Health Organization. 2023 WHO Review of Health in Nationally Determined Contributions and Long-Term Strategies: Health at the Heart of the Paris Agreement. World Health Organization; 2023.

- Thompson R, Lawrance EL, Roberts LF, Grailey K, Ashrafian H, Maheswaran H, Toledano MB, Darzi A. Ambient temperature and mental health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet Health. 2023;7–e589. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(23)00104-3

- Redvers N, Celidwen Y, Schultz C, Horn O, Githaiga C, Vera M, Perdrisat M, Mad Plume L, Kobei D, Cunningham Kain M, Poelina A, Nelson Rojas J, Blondin B. The determinants of planetary health: an Indigenous consensus perspective. Lancet Planetary Health. 2022;6:2. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00354-5

- Collins PY. What is global mental health?. World psychiatry: official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 2020;19(3), 265–266. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20728

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11). World Health Organization; 2022. Available from: https://icd.who.int/

- IPCC, 2023: Annex I: Glossary [van Diemen, R., J.B.R. Matthews, V. Möller, J.S. Fuglestvedt, V. Masson-Delmotte, C. Méndez, A. Reisinger, S. Semenov (eds.)]. In: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp. 2215-2256, doi: 10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.006.